|

History

Shakyamuni to China

The history of Zen Buddhism started with Gautama Shakyamuni’s awakening to the True Dharma, the Buddha-nature inherent in all

beings. The lineage of the Zen School is traditionally regarded as having commenced with Shakyamuni’s transmission of the Mind Seal

( inka shomei 印可証明) to his disciple Mahakashyapa (see “Buddha Mind School”). With Shakyamuni’s recognition of

Mahakashyapa began the “direct transmission from

master to disciple” that Zen emphasizes as the particular characteristic of

its history as a tradition.

Mahakashyapa was followed in the traditional Zen lineage by Ananda, the

Buddha’s cousin and attendant who had failed to attain enlightenment while

the Buddha was alive, but who awakened to the Buddha Mind through the

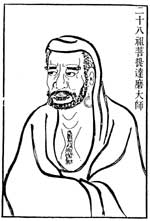

guidance of Mahakashyapa. The Indian lineage continued until the

twenty-eighth patriarch, Bodhidharma, who transmitted the Zen teachings to

China in the early sixth century. Bodhidharma was succeeded by his disciple Huike 慧可

(487–593), a Chinese monk who, when he first visited the master, is said to

have demonstrated his determination by cutting off his arm. His

enlightenment is traditionally described as follows: Mahakashyapa was followed in the traditional Zen lineage by Ananda, the

Buddha’s cousin and attendant who had failed to attain enlightenment while

the Buddha was alive, but who awakened to the Buddha Mind through the

guidance of Mahakashyapa. The Indian lineage continued until the

twenty-eighth patriarch, Bodhidharma, who transmitted the Zen teachings to

China in the early sixth century. Bodhidharma was succeeded by his disciple Huike 慧可

(487–593), a Chinese monk who, when he first visited the master, is said to

have demonstrated his determination by cutting off his arm. His

enlightenment is traditionally described as follows:

Huike, the Second Patriarch, said to Bodhidharma, “My mind is not yet at

rest. Master, I implore you, set my mind to rest.” The master replied,

“Bring your mind here and I’ll set it to rest for you.” Huike said, “I have

searched for my mind, but am unable to find it.” “There,” said the master,

“I have set your mind to rest.”

From Huike the Chinese patriarchate continued through Sengcan 僧璨 (the Third

Patriarch; d. 606?), Daoxin 道信 (the Fourth Patriarch; 580–651), and Hongren

弘忍 (the Fifth Patriarch; 600-674), to Huineng 慧能 (the Sixth Patriarch;

738ー713). Under Huineng, Zen took on a distinctly Chinese character with an

emphasis on “sudden awakening” to the Buddha-nature inherent in every being.

Huineng’s intuition of the universal nature of Buddha Mind was already

expressed in the story of his first encounter with the Fifth Patriarch:

It is said that when Huineng arrived at the monastery, Hongren asked about his origins.

Huineng replied that he had come from southern China. Hongren said that a

barbarian from the south can never become a Buddha. When Huineng responded,

“There is no north and south in Buddha nature,” Hongren sensed Huineng’s

ability and put him to work at the monastery as a rice huller. From Huike the Chinese patriarchate continued through Sengcan 僧璨 (the Third

Patriarch; d. 606?), Daoxin 道信 (the Fourth Patriarch; 580–651), and Hongren

弘忍 (the Fifth Patriarch; 600-674), to Huineng 慧能 (the Sixth Patriarch;

738ー713). Under Huineng, Zen took on a distinctly Chinese character with an

emphasis on “sudden awakening” to the Buddha-nature inherent in every being.

Huineng’s intuition of the universal nature of Buddha Mind was already

expressed in the story of his first encounter with the Fifth Patriarch:

It is said that when Huineng arrived at the monastery, Hongren asked about his origins.

Huineng replied that he had come from southern China. Hongren said that a

barbarian from the south can never become a Buddha. When Huineng responded,

“There is no north and south in Buddha nature,” Hongren sensed Huineng’s

ability and put him to work at the monastery as a rice huller.

Later Hongren, wishing to name a successor, asked the monks to write a verse

expressing their understanding. The first verse was that of the senior monk,

Shenxiu 神秀 (605–706), who wrote, “The body is the Bodhi tree, the mind is

like a clear mirror. At all times strive to polish it, and let no dust

collect.” The illiterate Huineng, after hearing another monk recite

Shenxiu’s verse, responded with a verse expressing the Zen understanding of

the essential nonsubstantiality of mind: “Originally there is no tree of

enlightenment, nor is there a stand with a clear mirror. From the beginning

not a single thing exists; where is there for dust to collect?” Hongren

approved of Huineng’s verse and transmitted the patriarchate to him.

The teaching line of Huineng flourished, eventually forming the mainstream

of Chinese Zen and giving rise to the various traditions known as the Five

Houses and Seven Schools.

Three generations after Huineng, the master Baizhang Huaihai 百丈懷海 (J., Hyakujo Ekai; 749–814)

laid the foundations of the Zen monastic life, with manual labor as a

central part of the daily schedule (he is known for his famous dictum, “A

day of no work—a day of no eating”). His monastic rule, the Chanlin qinggui

禪林清規, no longer exists in its original form, but all subsequent forms of Zen

monasticism have been influenced by his ideas on meditation practice and

architectural design for the Zen monastery. Three generations after Huineng, the master Baizhang Huaihai 百丈懷海 (J., Hyakujo Ekai; 749–814)

laid the foundations of the Zen monastic life, with manual labor as a

central part of the daily schedule (he is known for his famous dictum, “A

day of no work—a day of no eating”). His monastic rule, the Chanlin qinggui

禪林清規, no longer exists in its original form, but all subsequent forms of Zen

monasticism have been influenced by his ideas on meditation practice and

architectural design for the Zen monastery.

Over the centuries two basic approaches to the practice of zazen emerged:

“silent illumination Zen” 黙照禪, which came to be associated principally with

the Caodong (J. Soto) school, and “koan-introspecting Zen” 看話禪, which came

to be associated principally with the Linji school.

Silent illumination Zen was promoted in the Tang dynasty by Shishuang

Qingzhu 石霜慶諸 (J., Sekiso Keisho, 807–888), who taught, “Cease and stop....

One thought—ten-thousand years. Be like a cold incense burner in an

abandoned temple.” Koan Zen developed when masters started to use the words

and actions of former Zen monks as expedients to help precipitate or clarify

understanding in the own students. It is advocated particularly by masters

like Fenyang Shanzhao 汾陽善昭 (J., Fun’yo Zensho; 947–l024), Yuanwu Keqin 圜悟克勤

(J., Engo Kokugon, 1063–1135), and Dahui Zonggao 大慧宗杲 (J., Daie Soko;

1089–1163).

The Five Houses and Seven Schools

Among the successors of the Sixth Patriarch Huineng,

the two masters Nanyue Huairang 南嶽懷讓 (Nangaku

Ejo; 677–744) and Qingyuan Xingsi 青原行思 (J., Seigen Gyoshi; d. 740) were of

especial importance in the subsequent history of Zen, for it was their

lineages that produced all the later traditions of mainstream Chinese Zen ,

known, collectively, as the Five Houses. The Five Houses were:

1) the Linji 臨濟 (J., Rinzai) school, established by Nanyue Huairang’s

descendent Linji Yixuan 臨濟義玄 (J., Rinzai Gigen; d. 867);

2) the Guiyang 潙仰 (J., Igyo) school, established by Nanyue Huairang’s

descendant Guishan Lingyou 潙山靈祐 (J., Isan Reiyu, 771–853) and his disciple

Yangshan Huiji 仰山慧寂 (J., Kyozan Ejaku; 807–883);

3) the Caodong 曹洞 (Jap., Soto) school, established by Qingyuan Xingsi’s

descendant Dongshan Liangjie 洞山良价 (J., Tozan Ryokai; 807–869) and Dongshan’s

student Caoshan Benji 曹山本寂 (J., Sozan Honjaku, 840–901); 3) the Caodong 曹洞 (Jap., Soto) school, established by Qingyuan Xingsi’s

descendant Dongshan Liangjie 洞山良价 (J., Tozan Ryokai; 807–869) and Dongshan’s

student Caoshan Benji 曹山本寂 (J., Sozan Honjaku, 840–901);

4) the Yunmen 雲門 (J., Unmon) school, established by Qingyuan Xingsi’s

descendant Yunmen Wenyan 雲門文偃 (J., Unmon Bun’en; 864–949);

5) the Fayan 法眼 (J., Hogen) school, established by Qingyuan Xingsi’s

descendant Fayan Wenyi 法眼文益 (J., Hogen Mon’eki, 885–958).

The Linji school was further divided into the Yangqi (Yogi) and Huanglong (Oryo)

teaching lines, which, together with the Five Houses, formed the Seven

Schools.

Although the Five Houses taught essentially the same Dharma as that

transmitted through the generations of meditation masters from the time of Shakyamuni Buddha, their respective teaching styles differed according to

the personalities of their founders. To summarize:

1. The Linji school was known for its emphasis on sudden awakening, its

occasionally rough teaching techniques (such as use of the shout and the

stick), and, from Song-dynasty times, its extensive use of the koans.

2. The Guiyang school was known for its combination of Guishan Lingyou’s

teaching on the unity of principle and function with Yangshan Huiji’s use of

esoteric symbols like the circle-figure 圓相. The school later declined, and

disappeared after about 150 years.

3. The Caodong school was known for its aversion to worldly involvement and

its emphasis on long sitting in “silent illumination” zazen (though koans

were also used). The Five Ranks doctrine was an important aspect of its

teaching. In Japan there is a particular stress on ritual practice and

the activities of everyday life. In China the school declined and

disappeared in Ming times (1368–1644); the school remains active in Japan.

4. The Yunmen school flourished greatly for several centuries after the time

of its founder, Yunmen Wenyan, especially among the educated elite. After

several centuries it declined, however, and disappeared during the Yuan era

(1280–1368). It was known for its terse, penetrating use of words, as

exemplified by the so-called “one-word barriers” of Yunmen.

5. The Fayan school was known for its literary efforts, whitch gave rise to the

classical Zen biographies and helped lay the foundations of koan Zen. Fayan-school

masters were active in the development of the koans, and in attempts to

combine zazen training with nenbutsu practice and Tiantai doctrine. In part

because of its syncretistic tendencies, it disappeared as a distinct school

after several generations, but its methods of koan work were assimilated into Linji Zen.

The Transmission of Zen to Japan

The Zen teachings

first reached Japan during the seventh century with the Japanese Hosso

school monk Dosho 道昭 (629–700), who traveled to Tang-dynasty China in 653.

There, in addition to his study of Yogacara under the great translator-monk

Xuanzang 玄奘 (602–664), he learned Zen meditation from Huiman 慧滿 (7 c.), a

disciple of the Second Patriarch, Huike. After returning to Japan he opened

the country’s first Zen meditation hall at Gango-ji 元興寺 in Nara. He was

followed in the eighth century by the Chinese Vinaya-school monk Daoxuan

道璨, who taught Zen meditation in addition to the vinaya. In the ninth

century the Chinese Zen master Ikong 義空 (J., Giku) came to Japan and taught for a

number of years before returning to China. None of these monks succeeded in

establishing a lasting lineage, however.

The Zen school took firm root in Japan only during the Kamakura era

(1192–1333) and early part of the Muromachi era (1336–1573), when changes in

the religious consciousness of the country led to greater interest in

various practices leading to personal liberation.

The first Japanese monk

to transmit the Rinzai teachings to Japan was the Japanese Tendai monk Myoan

Yosai [Eisai] 明菴榮西 (1141–1215). Born in present

Okayama Prefecture, he became a Tendai-school monk at the age of eleven and

studied the esoteric teachings of that tradition. He went to the Tendai

headquarters on Mt. Hiei two years later, and was ordained in 1154. In 1168

he traveled to China, where he studied the Tiantai teachings and practiced

Tiantai meditation methods for six months before returning to Japan. The first Japanese monk

to transmit the Rinzai teachings to Japan was the Japanese Tendai monk Myoan

Yosai [Eisai] 明菴榮西 (1141–1215). Born in present

Okayama Prefecture, he became a Tendai-school monk at the age of eleven and

studied the esoteric teachings of that tradition. He went to the Tendai

headquarters on Mt. Hiei two years later, and was ordained in 1154. In 1168

he traveled to China, where he studied the Tiantai teachings and practiced

Tiantai meditation methods for six months before returning to Japan.

Twenty years later, in

1187, he once again sailed for China, hoping to make a pilgrimage to India,

the home of Buddhism, in order further his goal of restoring Japanese Zen to

its original ideals. When the Chinese government refused him permission to

travel beyond its borders, Eisai made his way to Mount Tiantai and

undertook the practice of Linji (Rinzai) Zen with the Huanglong (Oryo) 黄龍

lineage master Xuan Huaichang 虚庵懷敞 (J., Koan Esho; n.d.), under whom he studied both

meditation and the vinaya.

In 1191 Eisai returned to

Japan, bringing not only the Rinzai Zen teachings but also the practice of

tea-drinking. He founded the monastery Shofuku-ji on the island of Kyushu,

avoiding the capital of Kyoto for the time being because of opposition to

the Zen teachings from the older established sects of Tendai and Shingon.

Later he did go to the capital to answer charges made against him by the

older schools, presenting his arguments in his chief work, the Kozen

Gokokuron (Propagation of Zen for protection of the nation). In 1199 he went

to Kamakura to assume the abbacy of the temple Jufuku-ji 壽福寺, built for him

by the Kamakura Shogunate. In 1202 he agreed to become abbot of the new

temple Kennin-ji in Kyoto, where, until the end of his life in 1215, he

taught a combination of Zen meditation with Tendai and Shingon ritual.

Although Eisai’s Oryo lineage did not continue long, he was important in

setting the stage for the restoration of monastic discipline and the

establishment of Zen meditation practice.

The transmission of the

Zen school to Japan continued after the time of Eisai through Japanese monks

who practiced Zen in China and Chinese masters who settled in Japan. Zen

tradition has it that the teachings were conveyed by a total of forty-six

masters, of whom twenty-four established lineages lasting at least a few

generations. Among these, the sole Rinzai lineage to flourish to the present

day is the so-called Otokan lineage of Nanpo Jomyo 南浦紹明 (1235ー1308), usually

known as Daio Kokushi 大應國師; his student Shuho Myocho 宗峰妙超 (1282-1337),

usually known as Daito Kokushi 大燈國師; and Shuho’s student Kanzan Egen 關山慧玄

(1277–1360). The term Otokan comes from the “o” of Daio, the “to” of Daito,

and the “kan” of Kanzan). This lineage has largely shaped Rinzai Zen

practice in Japan, and, through the eighteenth-century master Hakuin Ekaku,

includes every Rinzai Zen master in Japan today.

Nanpo Jomyo was a native

of Abe in present Shizuoka Prefecture. He entered the monkhood at the age of

fifteen, and at eighteen entered the monastery of Kencho-ji 建長寺, in the

shogun’s capital at Kamakura, to study under Lanxi Daolong 蘭溪道隆 (J., Rankei

Doryu; 1213-1278). In 1259 went to

China to study under Xutang Zhiyu 虚堂智愚 (J., Kido Chigu; 1185–1269), in

present-day Zhejiang. He received Xutang’s seal of transmission in 1265, and

returned to Japan in 1267. After spending several more years with his old

teacher Lanxi in Kamakura, he was appointed abbot of Kotoku-ji 興徳寺 on the

island of Kyushu in 1270. Three years later he became priest of Sofuku-ji 崇福寺

in nearby Dazaifu. There he lived and taught for thirty-three years, until

he was called to Kyoto in 1305 and appointed abbot of Manju-ji 萬壽寺. In 1307

he was appointed priest of Kencho-ji, where he died on 29 December 1308. He

was awarded the posthumous title National Teacher Enzu Daio 圓通大應國師.

Shuho Myocho was a native

of Harima in the region of present-day Hyogo. He was ordained at Enkyo-ji

圓鏡寺 on Mount Shosha at the age of eleven and studied Tendai doctrine. In

1301 he became a student of Koho Kennichi 高峰顯日 (1241–1316) at Manju-ji 萬壽寺

in Kamakura, then in 1304 went to Kyoto to study under Nampo Jomyo,

accompanying Nanpo to Kamakura when Nanpo was appointed abbot of Kencho-ji

in 1308. Just ten days after arriving at Kencho-ji, Myocho had a

breakthrough with the koan known as “Yunmen’s ‘Barrier’.” After Nanpo died

several months later, Shuho retumed to Kyoto and, according to legend, spent

twenty years living with beggars under the Gojo Bridge. Eventually Emperor Hanazono 花園 (r. 1308–1318), deciding to find him, went to the area with a

basket of melons and said to the beggars, “Take this melon without using

your hands.” One beggar replied, “Give it to me without using your hands,”

and the emperor knew this was Shuho.

In fact, Shuho appears to have spent

his years of seclusion at two small temples, Ungo-ji 雲居寺 in eastern Kyoto

and Daitoku-ji 大徳寺 in the northwestern part of the capital. The latter

temple was soon enlarged with the aid of the imperial court, and Shuho was

called to lecture before Emperor Hanazono, and, later, Emperor Go-Daigo 後醍醐

(r. 1318–1339). Shuho resided and taught at Daitoku-ji for the rest of his

life. At the time of his death Shuho forced his crippled leg into the full

lotus position (which broke the leg), wrote his death poem, and passed away.

Kanzan Egen, third in the Otokan lineage, was a native of Shinano in

present-day Nagano Prefecture; his family name was Takanashi. He received

ordination at Kencho-ji 建長寺 under the priest Toden Shikei 東傳士啓; in 1307 he

met Nanpo Jomyo, from whom he received the name Egen 慧玄. After Nanpo died in

1309, Egen returned to his native place until, in 1327, he met Nanpo’s

student Shuho Myocho and began his practice under him. In 1330 he

experienced a deep enlightenment. After receiving transmission from Myocho,

Kanzan is said to have gone to the mountain village of Ibuka in present-day

Gifu Prefecture, where he worked as a laborer and deepened his realization.

1337 he was called back to the capital and installed as the founding priest

of Myoshin-ji 妙心寺. There he taught a few students as well as the cloistered

emperor Hanazono. Kanzan is known for his austere lifestyle, and is said to

have died dressed in his pilgrimage clothes, standing under a tree.

Other important early Rinzai masters were:

Enni Ben’en 圓爾辯圓 (1201–1280) was born in Suruga, present Shizuoka

Prefecture, entered a temple at five and commenced Tendai studies at eight.

At eighteen he entered monastic life at the great Tendai temple Mii-dera,

and took the precepts at Todai-ji in Nara. His wide-ranging studies included

Confucianism, Abhidharma thought, and the exoteric and esoteric Tendai

teachings. In 1235 he left for a seven-year stay in China, where he

practiced under the eminent master Wuzhun Shifan 無準師範 (J., Bujun Shipan; 1177–1249). In 1241,

after receiving the seal of enlightenment from Wuzhun, Enni returned to

Japan and took up residence in Kyushu, where he established a number of Zen

monasteries. In 1243 the chancellor Kujo Michiie 九条道家 (1192–1252) invited

Enni to serve as the founding priest of Tofuku-ji 東福寺, a great Zen temple

planned by Michiie to compare in grandeur to the great temples of Todai-ji

東大寺 and Kofuku-ji 興福寺 in Nara. Enni was well prepared to lead the Shingon,

Tendai, and Zen practices that comprised the monastic training at Tofuku-ji

at that time. Enni also served as the tenth abbot of Kennin-ji,

simultaneously with his duties at Tofuku-ji. He was awarded the posthumous

title National Teacher Shoichi 聖一國師 by Emperor Hanazono. Though Enni’s

teachings combined Zen with Tendai and Shingon, he was instrumental in

helping the Zen school, still relatively new to Japan at the time, win

increasing acceptance and respect in the capital.

Shinchi Kakushin 心地覺心 (1207–1298), also known as National Teacher Hatto

Enmyo 法燈圓明國師, was a native of Shinshu (present Nagano Prefecture); his

family name was Tsunezumi. He became a monk at eighteen, and at twenty-nine

received the full precepts at the temple Todai-ji 東大寺 in the ancient capital

of Nara. Following this he studied esoteric Buddhism on Mount Koya 高野,

headquarters of the Japanese Shingon 眞言 school, where he met the Rinzai Zen

master Taiko Gyoyu 退耕行勇 (1163–1241), under whom he trained from 1239 to 1241

at the temples Kongo-zanmai-in 金剛三昧院 on Mount Koya and Jufuku-ji 壽福寺 in

Kamakura. In 1249, after further training with other masters, he embarked

for China to study under Wuzhun Shifan 無準師範 (1177–1249). Finding that Wuzhun

had died, Kakushin visited various important Buddhist centers until a fellow

Japanese monk named Genshin 源信 directed him to the Zen master Wumen Huikai

無門慧開 (J., Mumon Ekai; 1183–1260) of the temple Huguo Renwang si 護國仁王寺, near the city of

Hangzhou. In a well-known story, Kakushin, when asked by Wumen, “My place

has no gate; how did you get in?” answered, “I entered from no-gate (wumen).”

After a mere six months Kakushin received dharma transmission, along with

the gifts of a robe, a portrait of Wumen, and the Wumen guan 無門關 (Jap.,

Mumonkan), a collection of koans compiled by Wumen that has remained a

central text in Japanese Rinzai koan study. Following his return to Japan in

1254, Kakushin first resided on Mount Koya, then became abbot of the temple

Saiho-ji 西方寺 (later called Kokoku-ji 興國寺) in Yura, present Wakayama

Prefecture. He often lectured before the emperors Kameyama 龜山 (r. 1259–74) and

Go-Uda 後宇多 (r. 1274–87), and received from Kameyama the honorary title Zen

Master Hotto 法燈禪師; following his death he was designated National Teacher

Hotto Enmyo 法燈圓明國師 by Emperor Go-Daigo 後醍醐 (r. 1319–1339). Kakushin is

regarded as the founder of the influential Hotto 法燈 (also Hatto) line of

Rinzai Zen and of the Japanese Fuke school 普化宗, a tradition of largely lay

practicers who wandered about the country playing the shakuhachi 尺八, a

bamboo flute whose music was regarded as an aid to enlightenment.

Lanxi Daolong 蘭溪道隆 (J. Rankei Doryu; 1213–1278) was a native of the

present-day Sichuan region of China. He entered temple life at the age of

thirteen, studying under the masters Wuzhun Shifan 無準師範 (1177–1249), Chijue

Daochong 癡絶道冲 (J., Chizetsu Dochu; 1169–1250), and others, and succeeding to the dharma of Wuming Huixing 無明慧性 (J.,

Mumyo Esho; 1162–1237). In 1246 he and several of his disciples

came to Japan, first to the southern island of Kyushu and later, at the

invitation of the regent Hojo Tokiyori 北条時頼 (1227–1263), to the city of Kamakura,

the capital of the shogunate. There in 1253, under Tokiyori’s patronage, he

was named founding priest of Kencho-ji 建長寺, Japan’s first true Rinzai Zen

monastery. Later Lanxi moved to Kyoto and was appointed abbot of Kennin-ji,

Yosai’s part-Zen, part-Tendai temple that Lanxi reorganized as a center of

pure Zen training. After returning to Kamakura he served again as abbot of

Kencho-ji until, in 1265, he was falsely accused of spying for the Mongols

and exiled for a time. He was later allowed to reside at Jufuku-ji and, just

before his death, was reinstated to his position at Kencho-ji. Following his

death he was granted the posthumous title Meditation Master Daikaku 大覺禪師,

the first time anyone in Japan had received the “meditation master” title.

Wuxue Zuyuan 無學祖元 (J., Mugaku Sogen; 1226–1286) was a student of Wuzhun

Shifan 無準師範 (1177–1249) in China. He was invited to Japan by the Kamakura

regent, Hojo Tokimune 北条時宗(1251-1284), arriving in 1279. After serving for a time as abbot

of Kencho-ji, he was appointed founding abbot of the great monastery

Engaku-ji 圓覺寺, and there taught a number of influential Japanese monks.

Yishan Yining 一山一寧 (J.,

Issan Ichinei; 1247–1317) was a native of Taizhou in present-day

Zhejiang. Yining entered the temple Hongfusi 鴻福寺 as a child and, following

full ordination at Puguang si 普光寺, studied the teachings of the Vinaya and

Tiantai schools. He then turned to Zen and, after training under a number of

masters, became the dharma heir of Wanji Xingmi 頑極行彌(J., Gankyoku Gyomi; n.d.). In 1299, at the order

of the Yuan court, he came to Japan as part of a delegation to discuss peace

negotiations between China and Japan. Although the delegation was at first

detained by the Kamakura regent Hojo Sadatoki 北条貞時 (1271–1311) on suspicion of

spying, Yining ultimately won great favor from Sadatoki, who allowed him to

reside at the Kamakura Zen temples Kencho-ji, Engaku-ji, and Jochi-ji 淨智寺.

In 1313 he was invited by Emperor Go-Uda 後宇多 (r. 1274–87) to become abbot of

Nanzen-ji 南禪寺, the most important of the Kyoto Zen temples at that time,

where he served as a popular teacher of both clerics and laypeople until

the time of his death in 1317.

Muso Soseki 夢窓疎石 (1275–1351), also referred to as Muso Kokushi 夢窓國師, was a

native of Ise in present Mie Prefecture. Soseki was ordained at the age of

eight and first studied the esoteric teachings of the Tendai school. He

despaired of finding an answer to the question of life-and-death in the

Tendai doctrines after witnessing the painful death of his teacher, and

turned to Zen. He studied under various masters in Kyoto and Kamakura,

notably the Chinese master Yishan Yining and, later, Koho Kennichi 高峯謙日

(1241–1316), although he carried out most of his actual training alone in

remote rural areas. His enlightenment was confirmed by Kennichi, who

recognized him as a successor. Following this enlightenment he continued

training in the countryside for a further twenty years, until called to the

capital by Emperor Go-Daigo 後醍醐 (r. 1318–39) to become abbot of Nanzen-ji.

He later founded a number of temples in Kyoto and elsewhere, prominent among

them Rinsen-ji 臨川寺, Shokoku-ji 相國寺, and Tenryu-ji 天龍寺, the latter built, at

Muso’s urging, by the shogun Ashikaga Takauji 足利尊氏 (1305–58) in memory of

Go-Daigo and the others who perished during the civil war that brought the

Ashikaga family to power. Muso was also a central figure in the development

of Japanese Buddhist culture, leaving many poems and designing a number of

famous gardens, particularly those of Saiho-ji 西方寺 (the Moss Temple) and

Tenryu-ji 天龍寺 (now designated a United Nations World Heritage Site). He was a

dedicated meditation monk as well; the monastic rule that he established at Rinsen-ji

was one of the earliest such codes in Japan.

Bassui Tokusho 抜隊得勝 (1327-1387) was born in the town of Nakamura, in present

Kanagawa Prefecture. His father died when he was four. Perhaps as a result

he developed a deep sense of questioning regarding the true nature of the

self, and practiced meditation from early in life. He became a monk at the

age of twenty-nine but preferred to avoid temples, practicing in isolated

places. After attaining a certain degree of understanding he sought

confirmation with several masters, including Kozan Mongo 肯山聞悟 of Kencho-ji

and Fukuan Soki 復菴宗己 of Houn-ji, but was not satisfied with their responses.

On the advice of a friend, a Buddhist ascetic named Tokukei 徳瓊, Bassui

called upon the master Koho Kakumyo 孤峰覺明 (1271–1361) of Unju-ji 雲樹寺 in present

Shimane Prefecture. Koho’s questioning about the nature of Zhaozhou’s “Mu”

precipitated a deep understanding in Bassui, who was then thirty-two years

old. Bassui received transmission, but left Unju-ji after only sixty days,

visiting a number of other masters and residing in mountain huts as he

continued his training. He refused all students until he reached the age of

fifty. A large community quickly formed around him, and he decided to settle

near the town of Enzan in present Yamanashi Prefecture, where the local lord

had offered to build the temple Kogaku-an 向嶽庵 for him. Eventually a thousand

monks and lay devotees gathered around him. Bassui taught a style of Zen

that downplayed ritual, stressed the precepts, and focused on the

fundamental question, “What is the ‘I’ that sees with the eye and hears with

the ear?” Gozan and Rinka Monasteries

As we have seen, the eminent Zen masters who transmitted Zen to Japan soon

attracted the support of Japan’s leaders, who built for them great

monasteries in Kyoto and Kamakura. In the Kamakura period the major Zen

temples of Kamakura were ranked in the five mountain 五山 system—based on a Sung-dynasty Chinese

arrangement—with Kencho-ji at the top, followed, in order, by Engakau-ji,

Jufuku-ji, Jomyo-ji, and Jochi-ji. In the fourteenth century, as the center

of power moved more toward Kyoto, the ranking was revised. At the time of

Emperor Go-Daigo 後醍醐 (r. 1319–1339), the list placed the Kyoto temples of

Nanzen-ji, Tofuku-ji, and Kennin-ji in the top three places, followed by

Kencho-ji and Engaku-ji. The final system, arrived at by the Ashikaga

Shogunate in the late fourteenth century, established Five Mountain temple

systems in both Kyoto and Kamakura, with, in order from the top, Tenryu-ji,

Shokoku-ji, Tofuku-ji, Kennin-ji, and Manju-ji in Kyoto, and Kencho-ji,

Engaku-ji, Jufuku-ji, Jomyo-ji, and Jochi-ji in Kamakura. Nanzen-ji stood

above all of them as “the first Zen temple in the land.” This ranking

remains unchanged to this day. The Five Mountain temples were followed in

importance by the “Ten Temples” ( jissetsu), and the “Various Mountains” ( shozan),

to form an officially supported system of about 300 temples.

The large temples in the cultural and political centers of Japan became

seats of learning in Chinese literature, art, poetry, and political thought,

and as such exerted a wide influence on the educated classes in Japan. Out

of this cultural milieu emerged the literary movement known as gozan bungaku

五山文学,

which produced a number of noted poets and literary figures, all of who

wrote in Chinese. One of the central figures was the Chinese master Yishan

Yining 一山一寧 (J., Issan Ichinei; 1247–1317), who was equally versed in secular knowledge and Zen

thought. The lineage of Japanese master Muso Soseki also produced several

notable Gozan poets, notably Gido Shushin 義堂周信 (11325–1388) and Zekkai

Chushin 絶海中津 (1336–1405). With the decline of the Ashikaga shogunate in the

sixteenth century the influence of the Five Mountain monasteries waned.

Separate from the Five Mountain monasteries were the so-called Rinka

林下 (Forest)

monasteries, which remained outside of the official system. The two

principle Rinka Rinzai monasteries, Daitoku-ji and Myoshin-ji, were of the Otokan

lineage. There was a tendency in the Rinka monasteries to stress meditation

over the cultural pursuits of the Five Mountain monasteries, although

Daitoku-ji in particular became involved in cultural and political

activities

as a center of the tea ceremony in the sixteenth century.

An important abbot of Daitoku-ji during this period was Ikkyu Sojun 一休宗純

(1394-1481). Ikkyu was the son of a lady of the imperial court of Emperor

Go-Komatsu 後小松 (r. 1392–1412). When he was five years old, following his

mother’s expulsion from the court, he entered the temple Ankoku-ji 安國寺 in

Kyoto and there learned the essentials of Chinese poetry, refining his

knowledge during four years at Kennin-ji. Later he meditated with the

hermit-monk Ken’o 謙翁 at the temple Saikin-ji 西金寺; after Ken’o’s death he

became the disciple of Kaso Sodon 華叟宗曇 (1352–1428), who lived in a hermitage

on the shores of Lake Biwa. He spent nine years with Kaso, under whom he

experienced a deep awakening while meditating on the koan “Dungshan’s

Sixty Blows,” and later had another profound realization when hearing the

caw of a crow. After Kaso recognized him as his successor, Ikkyu spent a

further thirty years as a wandering monk living and associating with all

classes of the people. From the age of sixty he lived at Daitoku-ji, and was

eventually made abbot of that great temple. One of his accomplishments was

the restoration of the buildings of Daitoku-ji after their destruction

during the Onin Wars (1467–77). Ikkyu remains a popular figure to this day,

and is remembered for his wit and humor as well as his poetry and paintings.

Another influential Rinka master was Takuan Soho 澤庵宗彭 (1573–1645). Takuan

was born in Izushi, in present-day Hyogo Prefecture, to a samurai family. He

began his education at a local Pure Land temple, but soon moved to a larger

Zen temple, Sugyo-ji 宗鏡寺. In 1594 his teacher took him to Daitoku-ji, where

he practiced Zen under the master Shun’oku Soen 春屋宗園 (1529–1611). He later

studied under the

scholar-monk Monsai Tonin 文西洞仁 and the Zen master Itto Shoteki 一凍紹滴

(1539–1612), whose

successor he became. In 1609 he was named abbot of Nanshu-ji 南宗寺, a

Daitoku-ji school temple. After about ten years he left again on a life of

wandering, until a political disagreement with the shogunate, involving

government regulation of the Zen school, resulted in his exile and that of

the abbot of Daitoku-ji, Gyokushitsu Sohaku 玉室宗珀 (1572–1641). He spent his

years of exile in Kaminoyama in present-day Yamagata Prefecture. The exile

was revoked in 1632, and Takuan returned to Kyoto and later to his home

village of Izushi. However, not long thereafter his friendship with the

great swordmaster Yagyu Munenori 柳生宗矩 (1571–1646) led to an invitation to Edo (present-day

Tokyo), which he visited several times over the next few years, during which

time he developed good relations with the third Tokugawa shogun, Tokugawa

Iemitsu 徳川家光 (1604–1651). In 1639 Iemitsu built for him in Edo the temple Tokai-ji 東海寺, where

the master lived from that time. He wrote voluminously; his works include

writings on poetry, swordsmanship, and Buddhist docrine.

Revival Movements

Although each generation of Rinzai Zen masters in Japan produced figures

worthy of transmitting the Dharma lineages, by the sixteenth and seventeenth

centuries the overall tradition had much declined in vigor. However, in the

Edo period several important masters appeared who were responsible for a

great revival and popularization of Rinzai practice and teaching.

The first of these was Bankei Yotaku 盤珪永琢 (1622–1693). Bankei was born to a

Confucian family in Hamada, in present-day Hyogo Prefecture. His father, a

masterless samurai (ronin), practiced medicine in the town. At the age of

eleven, at the local Confucian school, Bankei came across the line “The

Great Learning illuminates Bright Virtue” in the classic Confucian text

Great Learning, and was seized with doubt as to what “bright virtue” might

be. He searched for a satisfactory answer for years, attending lectures and

practicing the nenbutsu, but remained unsatisfied. In 1638 he took up the

practice of Zen under the master Unpo Zenjo 雲甫全祥 (1568–1653) and continued

with him for several years. He then left on a pilgrimage from 1641 to 1645,

during which he practiced severe austerities; after returning to Unpo’s

temple, he took up residence in a hut and continued his intense meditation.

Finally he became so weak that he could no longer eat, and contracted a

severe illness. One day, after coughing up a mass of black phlegm against a

wall and watching it slide down, he had a sudden, profound realization that

all things are perfectly resolved in the Unborn. With that realization he

started to eat again and soon recovered his health.

In 1651 Bankei went to see the Chinese Zen master Daozhe Chaoyuan 道者超元 (J.,

Dosha Chogen; d.

1660), who had just arrived in Nagasaki. Daozhe confirmed Bankei’s

enlightenment and helped guide him to a still deeper realization. Bankei

respected Daozhe and remained with him for a year, but was still not fully

satisfied. He returned to the main island of Honshu for further meditation

practice, and later received transmission from Unpo’s successor, Bokuo Sogyu

牧翁祖牛 (d.1694). Subsequently he founded or restored many important temples, including Ryomon-ji 龍門寺 in present-day Himeji. He traveled widely from

Kyushu to Edo,

and gave sermons on the Dharma to thousands of followers, stressing in his

talks the importance of awakening to the Unborn.

The most important reviver of the Rinzai tradition, and in some respects the

greatest figure in Japanese Rinzai Zen, was Hakuin Ekaku 白隱慧鶴 (1686–1769).

Hakuin was a native of the village of Hara in present Shizuoka Prefecture.

As a young boy he displayed a remarkable memory and strong character, but is

said to have been terrified by images of hell. At the age of fifteen he

became a monk at the nearby temple Shoin-ji 松蔭寺. At the age of nineteen he

had a crisis that caused him to leave meditation training for several years

and devote himself to the study of literature, but later, upon reading how

the Chinese master Shishuang Chuyuan 石霜楚圓 (J., Sekiso Soen; 986–1039) kept

himself awake during his meditation at night by sticking his thigh with an

awl, he returned to his zazen practice with renewed determination. At

twenty-four he had an awakening upon hearing the sound of a temple bell, an

experience he deeped through training under the master Dokyo Etan 道鏡慧端

(1642–1721) of Shoju-an 正受庵 in what is now Nagano Prefecture. Further

training and experiences followed, even after he returned to Suruga as abbot

of Shoin-ji. His decisive spiritual breakthrough occurred when he was

forty-two years old. The most important reviver of the Rinzai tradition, and in some respects the

greatest figure in Japanese Rinzai Zen, was Hakuin Ekaku 白隱慧鶴 (1686–1769).

Hakuin was a native of the village of Hara in present Shizuoka Prefecture.

As a young boy he displayed a remarkable memory and strong character, but is

said to have been terrified by images of hell. At the age of fifteen he

became a monk at the nearby temple Shoin-ji 松蔭寺. At the age of nineteen he

had a crisis that caused him to leave meditation training for several years

and devote himself to the study of literature, but later, upon reading how

the Chinese master Shishuang Chuyuan 石霜楚圓 (J., Sekiso Soen; 986–1039) kept

himself awake during his meditation at night by sticking his thigh with an

awl, he returned to his zazen practice with renewed determination. At

twenty-four he had an awakening upon hearing the sound of a temple bell, an

experience he deeped through training under the master Dokyo Etan 道鏡慧端

(1642–1721) of Shoju-an 正受庵 in what is now Nagano Prefecture. Further

training and experiences followed, even after he returned to Suruga as abbot

of Shoin-ji. His decisive spiritual breakthrough occurred when he was

forty-two years old.

Hakuin was tirelessly active in teaching the dharma. He traveled widely,

lectured on many of the basic Zen texts, and produced a large body of

writings, both in vernacular Japanese and classical Chinese. He started

systematization of the Rinzai koan curriculum, and attacked what he regarded

as distortions of Zen training, such as “silent illumination” zazen and the

practice of nenbutsu by Zen monks. He stressed the importance of bodhicitta,

in both its aspects of personal enlightenment (kensho) and the saving of all

sentient beings. His lineage now includes all masters of Rinzai Zen in

Japan.

The two monks in Hakuin’s lineage most influential in completing the koan

reform begun by Hakuin were Inzan Ien 隱山惟琰 (1751–1814) and Takuju Kosen

卓洲胡僊 (1760–1833). Inzan was a native of Echizen, present-day Fukui

Prefecture. He became a monk at the age of nine, and at sixteen began his

study of Zen under the Bankei-line master Bankoku 萬國(n.d.). After

three years he went to Gessen Zen’e 月船禪慧 (1702–1781), under whom he studied

for seven years. In 1789 he went for further study under Gasan Jito 峨山慈棹

(1727–1797), Gessen’s former student and an eminent successor of Hakuin

Ekaku. After two years he received recognition from Gasan, and went on to

teach in various temples, including Myoshin-ji and Zuiryo-ji 瑞龍寺. His

vigorous, dynamic style of Zen became one of the two streams of Hakuin Zen,

along with that of Takuju Kosen.

Takuju was born in Tajima, near the present-day city of Nagoya. He became a

monk at the age of fifteen at the temple Soken-ji 總見寺, and set out on

pilgrimage at nineteen. The following year he became a disciple of Gasan

Jito after hearing him lecture near Edo. He received transmission from the

master after fourteen years. Returning to Soken-ji, he devoted the rest of

his life to teaching the detailed style of Zen that came to characterize his

lineage, the Takuju school. The Obaku School

While the Rinzai school was developing independently in Japan from

the thirteenth to the seventeenth centuries, the Chinese Linji school

continued to evolve in its own way. Among the most noticeable changes were

the incorporation of the Guiyang, Caodong, Yunmen, and Fayan schools into

the Linji school, and the admixture of Pure Land and esoteric elements into

Zen practice.

From before the Tokugawa period (1603–1868) Chinese Zen priests had lived in

the trading city of Nagasaki to serve the resident Chinese community there;

from the mid-seventeenth century Chinese Zen masters started to arrive at

the port to teach Zen as it was then practiced in China. The first to arrive

was Daozhe Chaoyuan 道者超元 (J., Doja Chogen, d. 1660), who taught in Nagasaki

from 1651 to 1658. However, the lineage that was to develop into the

Japanese Obaku school was that of the master Yinyuan Longqi 隱元隆琦 (J., Ingen

Ryuki, 1592–1673). From before the Tokugawa period (1603–1868) Chinese Zen priests had lived in

the trading city of Nagasaki to serve the resident Chinese community there;

from the mid-seventeenth century Chinese Zen masters started to arrive at

the port to teach Zen as it was then practiced in China. The first to arrive

was Daozhe Chaoyuan 道者超元 (J., Doja Chogen, d. 1660), who taught in Nagasaki

from 1651 to 1658. However, the lineage that was to develop into the

Japanese Obaku school was that of the master Yinyuan Longqi 隱元隆琦 (J., Ingen

Ryuki, 1592–1673).

Yinyuan was a native of Fuqing in present-day Fujian; his family name was

Lin. In his early life he was a farmer, but began spiritual training at the

age of twenty-three following a religious experience one night while sitting

under a tree. At the age of twenty-nine he entered the monkhood at the

temple Huangbo Wanfu si 黄檗萬福寺, then studied under a number of masters before

receiving transmission from Miyun Yuanwu 密雲圓悟 (J., Mitsu’un Engo; 1566–1642). When Miyun’s

student Feiyin Tongrong 費隠通容 (J., Hi’in Tsuyo; 1593–1661) assumed the abbacy of Huangbo Wanfu

si, Yinyuan became head monk under him and later was named Feiyin’s dharma

successor. Yinyuan subsequently served as abbot of several temples,

including Wanfu si.

In 1654 Yinyuan departed for Japan, landing in Nagasaki. There he became

abbot of Kofuku-ji 興福寺, and, the following year, also of nearby Sofuku-ji

崇福寺. Later in 1655 he was named abbot of Fumon-ji 普門寺 in present-day Osaka.

In 1661, with the support of the shogunate, a temple was founded for Yinyuan

in Uji, just south of Kyoto. Yinyuan named the new temple Manpuku-ji 萬福寺,

with the mountain-name Obaku-san 黄檗山, in honor of the community he had left

behind in China. Manpuku-ji was designed according to contemporary Chinese

temple architecture, and its rule followed the monastic code of its namesake

in China. In 1664 Yinyuan retired and was succeeded by his disciple Mu’an

Xingdao 木菴性瑫 (J., Mokuan Shoto, 1611–1684).

Manpuku-ji and the other monasteries established in Yinyuan’s lineage

remained strongly Chinese in character for many generations. The first

thirteen abbots of Manpuku-ji were all Chinese; the fourteenth abbot, Ryuto

Gento 龍統元棟 (1663–1746), was the first Japanese abbot, but he was followed by

a number of Chinese chief priests. The thirty-third abbot, Ryochu Nyoryu

良忠如隆 (1793–1868) was a Dharma successor of the important Hakuin-line master

Takuju Kosen; since that time the teachings of the school have become

increasingly similar to those of Japanese Rinzai Zen (all masters are now of

the Hakuin lineage), although many of the monastic customs of the Obaku

school remain distinctly those of Ming-dynasty Chinese Zen. Practices like

the nenbutsu and esoteric rituals have been retained, ceremonies such as

sutra-chanting are performed in the Chinese manner, and mealtime ettiquette

follows Chinese

customs. |

The history of Zen Buddhism started with Gautama Shakyamuni’s awakening to the True Dharma, the Buddha-nature inherent in all

beings. The lineage of the Zen School is traditionally regarded as having commenced with Shakyamuni’s transmission of the Mind Seal

(inka shomei 印可証明) to his disciple Mahakashyapa (see “Buddha Mind School”). With Shakyamuni’s recognition of

Mahakashyapa began the “direct transmission from

master to disciple” that Zen emphasizes as the particular characteristic of

its history as a tradition.

The history of Zen Buddhism started with Gautama Shakyamuni’s awakening to the True Dharma, the Buddha-nature inherent in all

beings. The lineage of the Zen School is traditionally regarded as having commenced with Shakyamuni’s transmission of the Mind Seal

(inka shomei 印可証明) to his disciple Mahakashyapa (see “Buddha Mind School”). With Shakyamuni’s recognition of

Mahakashyapa began the “direct transmission from

master to disciple” that Zen emphasizes as the particular characteristic of

its history as a tradition. Among the successors of the Sixth Patriarch Huineng,

the two masters Nanyue Huairang 南嶽懷讓 (Nangaku

Ejo; 677–744) and Qingyuan Xingsi 青原行思 (J., Seigen Gyoshi; d. 740) were of

especial importance in the subsequent history of Zen, for it was their

lineages that produced all the later traditions of mainstream Chinese Zen ,

known, collectively, as the Five Houses. The Five Houses were:

Among the successors of the Sixth Patriarch Huineng,

the two masters Nanyue Huairang 南嶽懷讓 (Nangaku

Ejo; 677–744) and Qingyuan Xingsi 青原行思 (J., Seigen Gyoshi; d. 740) were of

especial importance in the subsequent history of Zen, for it was their

lineages that produced all the later traditions of mainstream Chinese Zen ,

known, collectively, as the Five Houses. The Five Houses were:

Mahakashyapa was followed in the traditional Zen lineage by Ananda, the

Buddha’s cousin and attendant who had failed to attain enlightenment while

the Buddha was alive, but who awakened to the Buddha Mind through the

guidance of Mahakashyapa. The Indian lineage continued until the

twenty-eighth patriarch, Bodhidharma, who transmitted the Zen teachings to

China in the early sixth century. Bodhidharma was succeeded by his disciple Huike 慧可

(487–593), a Chinese monk who, when he first visited the master, is said to

have demonstrated his determination by cutting off his arm. His

enlightenment is traditionally described as follows:

Mahakashyapa was followed in the traditional Zen lineage by Ananda, the

Buddha’s cousin and attendant who had failed to attain enlightenment while

the Buddha was alive, but who awakened to the Buddha Mind through the

guidance of Mahakashyapa. The Indian lineage continued until the

twenty-eighth patriarch, Bodhidharma, who transmitted the Zen teachings to

China in the early sixth century. Bodhidharma was succeeded by his disciple Huike 慧可

(487–593), a Chinese monk who, when he first visited the master, is said to

have demonstrated his determination by cutting off his arm. His

enlightenment is traditionally described as follows: From Huike the Chinese patriarchate continued through Sengcan 僧璨 (the Third

Patriarch; d. 606?), Daoxin 道信 (the Fourth Patriarch; 580–651), and Hongren

弘忍 (the Fifth Patriarch; 600-674), to Huineng 慧能 (the Sixth Patriarch;

738ー713). Under Huineng, Zen took on a distinctly Chinese character with an

emphasis on “sudden awakening” to the Buddha-nature inherent in every being.

Huineng’s intuition of the universal nature of Buddha Mind was already

expressed in the story of his first encounter with the Fifth Patriarch:

It is said that when Huineng arrived at the monastery, Hongren asked about his origins.

Huineng replied that he had come from southern China. Hongren said that a

barbarian from the south can never become a Buddha. When Huineng responded,

“There is no north and south in Buddha nature,” Hongren sensed Huineng’s

ability and put him to work at the monastery as a rice huller.

From Huike the Chinese patriarchate continued through Sengcan 僧璨 (the Third

Patriarch; d. 606?), Daoxin 道信 (the Fourth Patriarch; 580–651), and Hongren

弘忍 (the Fifth Patriarch; 600-674), to Huineng 慧能 (the Sixth Patriarch;

738ー713). Under Huineng, Zen took on a distinctly Chinese character with an

emphasis on “sudden awakening” to the Buddha-nature inherent in every being.

Huineng’s intuition of the universal nature of Buddha Mind was already

expressed in the story of his first encounter with the Fifth Patriarch:

It is said that when Huineng arrived at the monastery, Hongren asked about his origins.

Huineng replied that he had come from southern China. Hongren said that a

barbarian from the south can never become a Buddha. When Huineng responded,

“There is no north and south in Buddha nature,” Hongren sensed Huineng’s

ability and put him to work at the monastery as a rice huller.  Three generations after Huineng, the master Baizhang Huaihai 百丈懷海 (J., Hyakujo Ekai; 749–814)

laid the foundations of the Zen monastic life, with manual labor as a

central part of the daily schedule (he is known for his famous dictum, “A

day of no work—a day of no eating”). His monastic rule, the Chanlin qinggui

禪林清規, no longer exists in its original form, but all subsequent forms of Zen

monasticism have been influenced by his ideas on meditation practice and

architectural design for the Zen monastery.

Three generations after Huineng, the master Baizhang Huaihai 百丈懷海 (J., Hyakujo Ekai; 749–814)

laid the foundations of the Zen monastic life, with manual labor as a

central part of the daily schedule (he is known for his famous dictum, “A

day of no work—a day of no eating”). His monastic rule, the Chanlin qinggui

禪林清規, no longer exists in its original form, but all subsequent forms of Zen

monasticism have been influenced by his ideas on meditation practice and

architectural design for the Zen monastery. 3) the Caodong 曹洞 (Jap., Soto) school, established by Qingyuan Xingsi’s

descendant Dongshan Liangjie 洞山良价 (J., Tozan Ryokai; 807–869) and Dongshan’s

student Caoshan Benji 曹山本寂 (J., Sozan Honjaku, 840–901);

3) the Caodong 曹洞 (Jap., Soto) school, established by Qingyuan Xingsi’s

descendant Dongshan Liangjie 洞山良价 (J., Tozan Ryokai; 807–869) and Dongshan’s

student Caoshan Benji 曹山本寂 (J., Sozan Honjaku, 840–901); The first Japanese monk

to transmit the Rinzai teachings to Japan was the Japanese Tendai monk Myoan

Yosai [Eisai] 明菴榮西 (1141–1215). Born in present

Okayama Prefecture, he became a Tendai-school monk at the age of eleven and

studied the esoteric teachings of that tradition. He went to the Tendai

headquarters on Mt. Hiei two years later, and was ordained in 1154. In 1168

he traveled to China, where he studied the Tiantai teachings and practiced

Tiantai meditation methods for six months before returning to Japan.

The first Japanese monk

to transmit the Rinzai teachings to Japan was the Japanese Tendai monk Myoan

Yosai [Eisai] 明菴榮西 (1141–1215). Born in present

Okayama Prefecture, he became a Tendai-school monk at the age of eleven and

studied the esoteric teachings of that tradition. He went to the Tendai

headquarters on Mt. Hiei two years later, and was ordained in 1154. In 1168

he traveled to China, where he studied the Tiantai teachings and practiced

Tiantai meditation methods for six months before returning to Japan.

The most important reviver of the Rinzai tradition, and in some respects the

greatest figure in Japanese Rinzai Zen, was Hakuin Ekaku 白隱慧鶴 (1686–1769).

Hakuin was a native of the village of Hara in present Shizuoka Prefecture.

As a young boy he displayed a remarkable memory and strong character, but is

said to have been terrified by images of hell. At the age of fifteen he

became a monk at the nearby temple Shoin-ji 松蔭寺. At the age of nineteen he

had a crisis that caused him to leave meditation training for several years

and devote himself to the study of literature, but later, upon reading how

the Chinese master Shishuang Chuyuan 石霜楚圓 (J., Sekiso Soen; 986–1039) kept

himself awake during his meditation at night by sticking his thigh with an

awl, he returned to his zazen practice with renewed determination. At

twenty-four he had an awakening upon hearing the sound of a temple bell, an

experience he deeped through training under the master Dokyo Etan 道鏡慧端

(1642–1721) of Shoju-an 正受庵 in what is now Nagano Prefecture. Further

training and experiences followed, even after he returned to Suruga as abbot

of Shoin-ji. His decisive spiritual breakthrough occurred when he was

forty-two years old.

The most important reviver of the Rinzai tradition, and in some respects the

greatest figure in Japanese Rinzai Zen, was Hakuin Ekaku 白隱慧鶴 (1686–1769).

Hakuin was a native of the village of Hara in present Shizuoka Prefecture.

As a young boy he displayed a remarkable memory and strong character, but is

said to have been terrified by images of hell. At the age of fifteen he

became a monk at the nearby temple Shoin-ji 松蔭寺. At the age of nineteen he

had a crisis that caused him to leave meditation training for several years

and devote himself to the study of literature, but later, upon reading how

the Chinese master Shishuang Chuyuan 石霜楚圓 (J., Sekiso Soen; 986–1039) kept

himself awake during his meditation at night by sticking his thigh with an

awl, he returned to his zazen practice with renewed determination. At

twenty-four he had an awakening upon hearing the sound of a temple bell, an

experience he deeped through training under the master Dokyo Etan 道鏡慧端

(1642–1721) of Shoju-an 正受庵 in what is now Nagano Prefecture. Further

training and experiences followed, even after he returned to Suruga as abbot

of Shoin-ji. His decisive spiritual breakthrough occurred when he was

forty-two years old.

From before the Tokugawa period (1603–1868) Chinese Zen priests had lived in

the trading city of Nagasaki to serve the resident Chinese community there;

from the mid-seventeenth century Chinese Zen masters started to arrive at

the port to teach Zen as it was then practiced in China. The first to arrive

was Daozhe Chaoyuan 道者超元 (J., Doja Chogen, d. 1660), who taught in Nagasaki

from 1651 to 1658. However, the lineage that was to develop into the

Japanese Obaku school was that of the master Yinyuan Longqi 隱元隆琦 (J., Ingen

Ryuki, 1592–1673).

From before the Tokugawa period (1603–1868) Chinese Zen priests had lived in

the trading city of Nagasaki to serve the resident Chinese community there;

from the mid-seventeenth century Chinese Zen masters started to arrive at

the port to teach Zen as it was then practiced in China. The first to arrive

was Daozhe Chaoyuan 道者超元 (J., Doja Chogen, d. 1660), who taught in Nagasaki

from 1651 to 1658. However, the lineage that was to develop into the

Japanese Obaku school was that of the master Yinyuan Longqi 隱元隆琦 (J., Ingen

Ryuki, 1592–1673).